From Reverence to Reflection: My Journey with the Orthodox Church and Interreligious Studies

Growing up in an Ethiopian Tewahedo Orthodox Church, christian family, religion was deeply interwoven with my childhood. My father was a deacon, and my grandfather served as a priest, both holding the esteemed position of Gebez (ገበዝ) at Embatezu St. Mary Church (እንዳማርያም እምባጤዙ), which stood just a stone’s throw from our home.

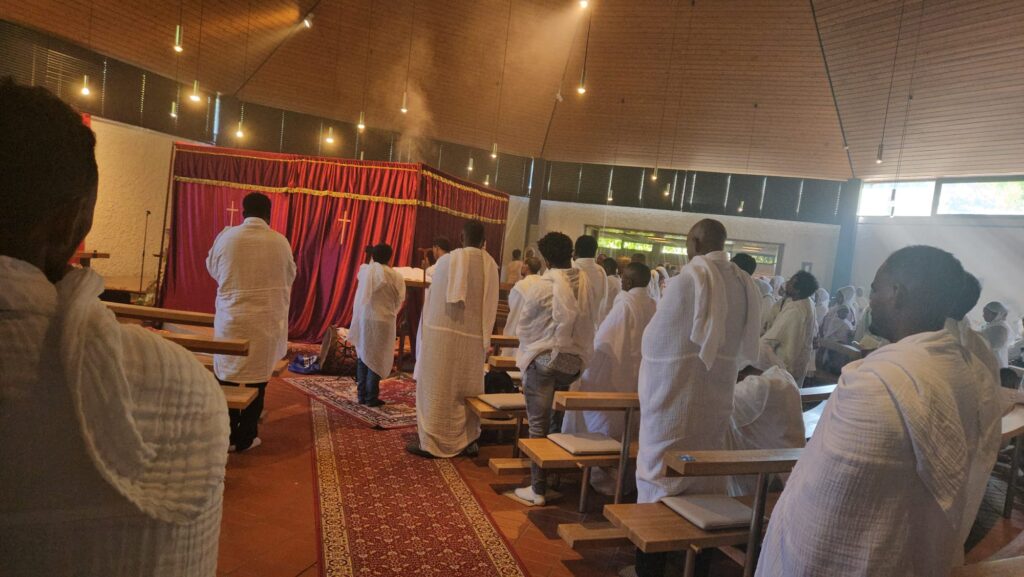

Until High School, I vividly remember being immersed in the life of the Church, going there regularly, attending the mahlet (ማህሌት), kidase (ቅዳሴ) occasionally, and observing the fasts with unwavering devotion. The Church, as a physical entity, was beyond a place of worship for me; it was the anchor of our daily lives. It stood along our path to school, work, or even shepherding. Each time we passed by, it was customary to stop, offer a prayer, and kiss the sacred wall (መንደቕ ቤተኽስያን) of the compound, especially via the major gates. Encounters with priests demanded reverence: I would kneel, kiss their feet, and receive blessings from their cross (መስቀል) or their hand, as is the religious practice.

Going to church was a form of competition among the kids in the village. Enduring the fasting season and attending the longest services earned you respect among your peers. Serving as an –atranose– carrying the sacred book read by the priests before the congregation, lighting the candles and making you a “good boy” in everyone’s eyes.

I particularly loved certain aspects of the church experience. The beautifully painted icons adorning the walls of St. Mary Church captured my attention; Jesus as a child on St. Mary’s hands, and the saints, especially St. George on his horse slaying the dragon. The artwork fascinated me, though I often wondered about the whiteness of the skin of most paintings unlike us, except for a few that resembled the beauty of Ethiopians, particularly in their expressive eyes.

The hymns (zema-ዜማ), the liturgical chant, accompanied by the rhythmic beats of the drums and sistrum (ከበሮን ጸናጽልን) filled the church with a sense of divine energy. The smoke from the incense rising in the air created an atmosphere of mystery and reverence. Watching the priests, decons, and other religious scholars (ሊቃውንቲ) enthusiastically strike the drums and perform liturgical dance in a distinctive, patterned rhythm was almost surreal, as if they were in a spiritual trance.

As a child, I used to sleep in the same room (hidmo, ህድሞ), and sometimes even in the same bed (መደብ፣ ዓራት፣ ዓራት ስቕሎ፣ ዋላ) with my father. One memory that has stayed with me is how he would suddenly wake up, especially on Sundays or saint days, to go to church during the night, often just after midnight, when it was his turn to serve. He was sometimes awakened by the sound of the rooster (which we used to tell time), or by the distant ringing of the church’s stone bell. These wake-ups would interrupt our cozy sleep, but they were also moments to step outside, relieve ourselves, and check that everything in the compound: the cattle, sheep, donkeys, calves, and chickens are safe.

I never felt disturbed. On the contrary, I was proud of his devotion to the church, though occasionally I was a little frightened after he left. Rarely, I would accompany him and spend the rest of the night in the church, mesmerized by the melodies of Ge’ez hymns (though I did not understand their meaning), and happy to see the soft glow of gas lamps and candlelight.

I also remember noticing that, on some nights when our father wanted to sleep with our mother, he would tell us he was going to church, though those times were much earlier than the usual midnight departures. I often sensed something was different. Later, I realized it was a clever trick, a gentle way of maintaining adult privacy when no explanation could yet make sense to a child of my age.

My name, Woldegiorgis, has a religious origin. Wolde (ወልደ/ውሉድ) means “son” in Ge’ez, the ancient liturgical language of northern Ethiopia (Tigray and Amhara) and Eritrea. Although today Ge’ez is no longer used in daily conversation, it remains the sacred language of the Ethiopian and Eritrean Tewahido Orthodox Churches. The second part, Giorgis (ጊዮርግስ), derives from the Greek “geṓrgios.” Combined, Woldegiorgis means “Son of George,” and is closely associated with the veneration of St. George, a revered figure in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. I was born on St. George’s Day, the 23rd of April in the Ethiopian calendar, which corresponds to May 1st in the Gregorian calendar.

Growing up, whenever I entered St. Mary’s Church in our village, I was drawn to the image of St. George. I would stand before the painting, captivated by the depiction of him slaying the dragon, something I understood as a form of Satan at the time. This personal connection deepened my admiration for the saint’s martyrdom and added religious significance to my name.

Discomfort Grew

But as I progressed through high school, something began to shift in my heart. I noticed behaviours among certain clergy that troubled me deeply. Their discriminatory treatment of the poor versus the rich during memorial services (Fit’hat, ፍትሓት), the reliance of some priests on superstitions such as witchcraft, the harshness of some exorcisms, and the prioritization of holy water (ጸበል) for illnesses to modern medicine, unsettled me most.

Credible reports and persistent rumours of embezzlement (ስርቂ), lack of transparency in the Church’s financial administration, dishonesty in everyday interactions, and even neglect of basic hygiene among some priests contributed to my growing disillusionment. However, what affected me most deeply was the dismissive and, at times, degrading attitude shown by certain priests toward households led by women.

I had once believed that clergy would serve as moral exemplars, embodying values of justice and compassion for all. But after losing my father when I was in grade nine, I experienced a different reality. Rather than offering support, some of the very priests I had respected failed to show the empathy or responsibility I expected.

When my father became seriously ill, I pleaded with neighbours and relatives, including respected priests, to help take him to the nearest health centre. Instead, they insisted on traditional rituals: making him inhale smoke from a burning calabash’s seeds (ፍረ ዓምሓም) to cast out what they believed was possession by the evil eye (ቡዳ). Of course, they accompanied it with spraying holy water and performing prayers.

I could not reconcile the superstitious practices with Christian teachings, particularly after I had attended biology and science classes in elementary school. I found the belief in “evil eye possession” to be unfounded and harmful. To this day, I believe my father might have survived had he received medical treatment as soon as possible.

This experience, among others, deeply shook the devotion I once had to the Church and forced me to question the moral integrity and pastoral responsibility of some of its clergy.

As a university student, and later as a journalist and educator, I began to examine more critically the role of the Orthodox Church in society and its historical influence. I came to question the binary oppositions (ክልቲኣዊ ዓለም) that religions promote, the context-blind interpretations they uphold, and the tacit biases present in the Ethiopian Orthodox church’s stance on Ethiopian nationalism. I struggled with the attitudes of some of its servants toward wealth, encouraging begging instead of nurturing a strong work ethic and fostering an organized system of welfare. I also felt its approach to modern education discouraging, with little urgency to adopt modern administration and financial management practices.

There are many other specific moments and stories that shaped these realizations of mine, which I hope to share as I revisit my memories. For now, I can only say that these experiences marked the beginning of my questioning, a journey that reshaped how I view religious institutions and the spiritual path laid before me.

On the other hand, I understand the power and influence of religious institutions in different societies, as well as the value of spiritual life for many people. Then, in the middle of all these mental processes, came the Tigray war!

Interest Re-energized

When the conflict in Ethiopia broke out in 2020, many bishops and archbishops of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, along with other prominent religious figures, openly supported the war, mobilized their followers to go and fight against the Tigray regional state of Ethiopia, contributed financially, and disseminated propaganda in favour of the federal/central government of Ethiopia. Like every other civil Tigrayan, priests and deacons of Tigrayan origin living outside Tigray were hunted and handed over to the police by church clergies all over the country, just because of their Tigrayan identity.

I was shocked and in disbelief!

The war forced me to flee the country and live in Kenya as an exiled journalist. Our media outlet in Addis Ababa was shut down, several of my colleagues were arrested, and I became a target both as a journalist and as an ethnic Tigrayan.

After more than a year of practising journalism online (which I still occasionally do) and producing radio content from Nairobi, I joined Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich in 2022 to pursue a PhD in Media Anthropology. My research explores the weaponisation of hate speech during the Tigray war in Ethiopia. As part of my digital ethnographic research, I also examine how religious figures produced or amplified hate speech online and through mainstream media. This became a motivating factor for me to commit my time to studying religion and to develop an interest in exploring it further.

In 2024, a friend at LMU introduced me to the Institute for Interreligious and Intercultural Encounter (OCCURSO), which houses the College of Interreligious Studies in Munich. The institute offers a basic certificate programme and is situated within the St. Boniface Monastery, where it also provides rental accommodation for its students.

Life, Lectures and Intercultural Encounters at the College

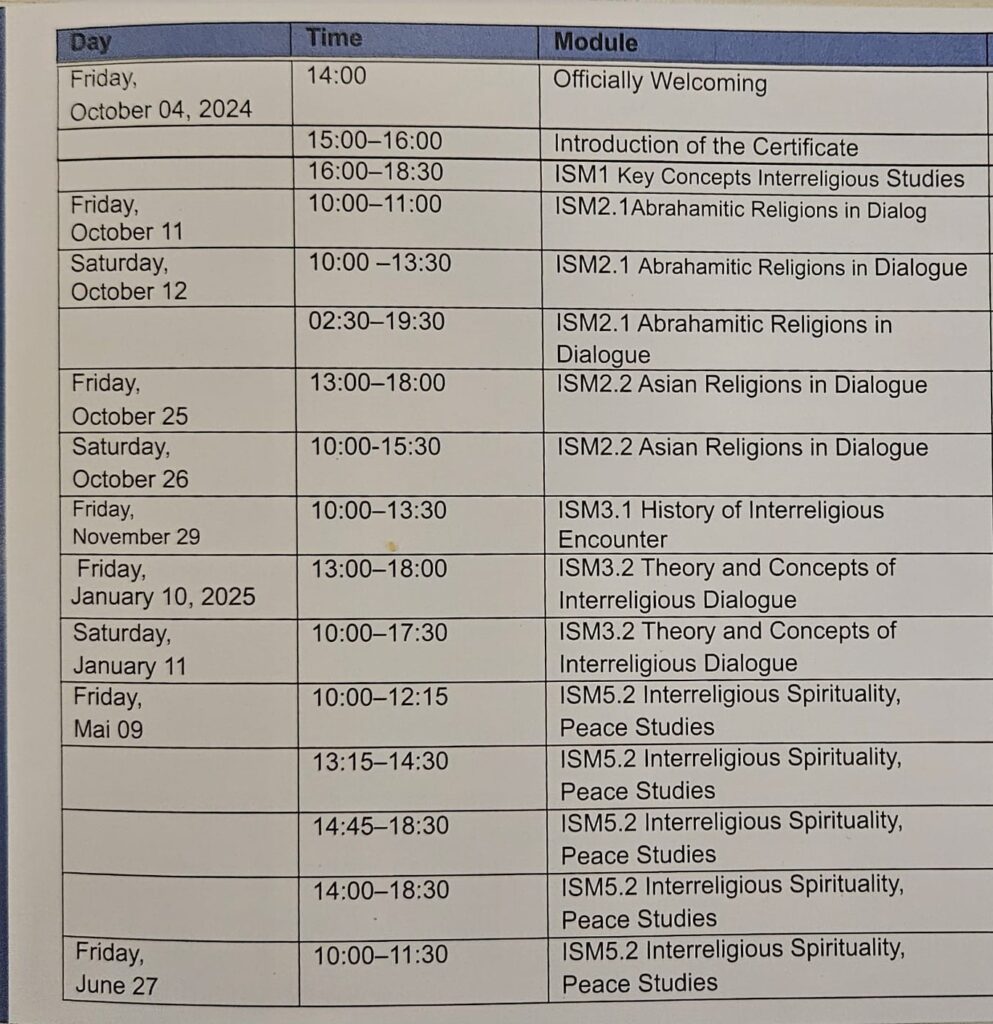

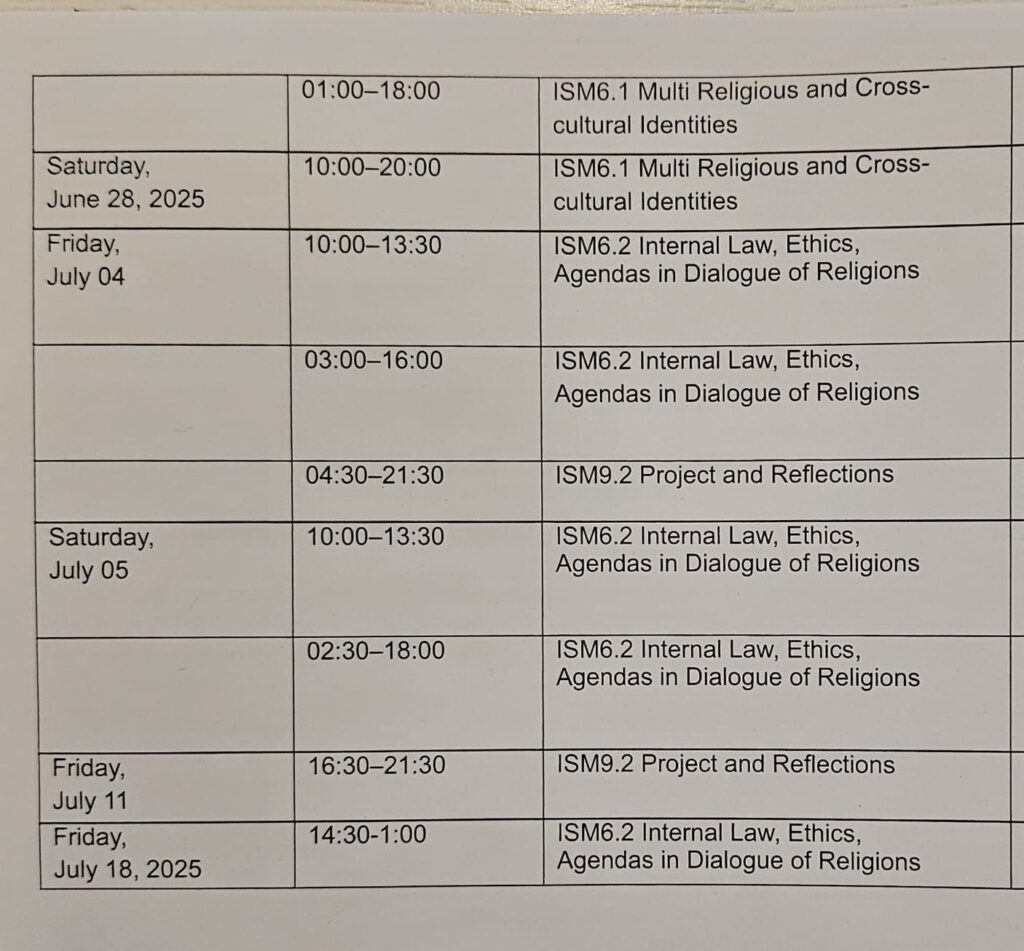

From June 2024 to November 2025, I lived at the College of Interreligious Studies and attended several courses as part of the Basic Certificate Programme. I studied alongside a small, diverse group of up to 14 students from various religious and cultural backgrounds, while simultaneously pursuing my PhD research.

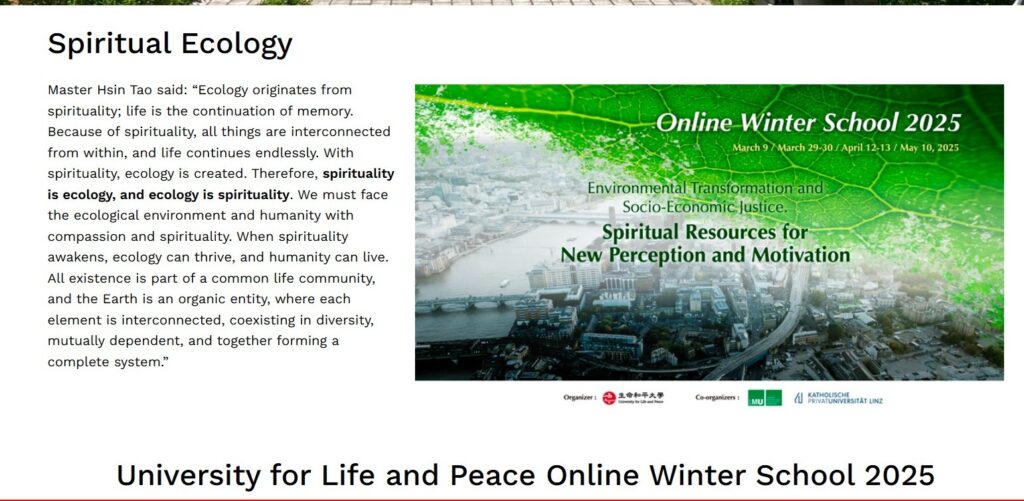

Spiritual Ecology: Online Winter School Program

To complement my interreligious studies at OCCURSO and driven by personal curiosity, I applied for an internship and was accepted into the 2025 Winter School on Spiritual Ecology, organised by the University of Life and Peace (Myanmar) in collaboration with Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich (LMU) and the Catholic University of Linz, Austria. I attended six full-day sessions covering topics such as the Introduction to Spiritual Ecology and Consciousness Development, Models for Sustainable Economic and Social Lifestyles, and the Application of Spiritual Ecology and Permaculture to Address Global Challenges and Promote Transformation. The programme was themed: “Environmental Transformation and Socio-Economic Justice: Spiritual Resources for New Perception and Motivation.” As part of the programme, I wrote a short essay on what and how journalists in Tigray, Ethiopia, especially environmental journalists, can incorporate the concepts and principles of spiritual ecology into their reporting.

My Interreligious Learning Process: Reflection and Sharing Experience through the Photovoice Method

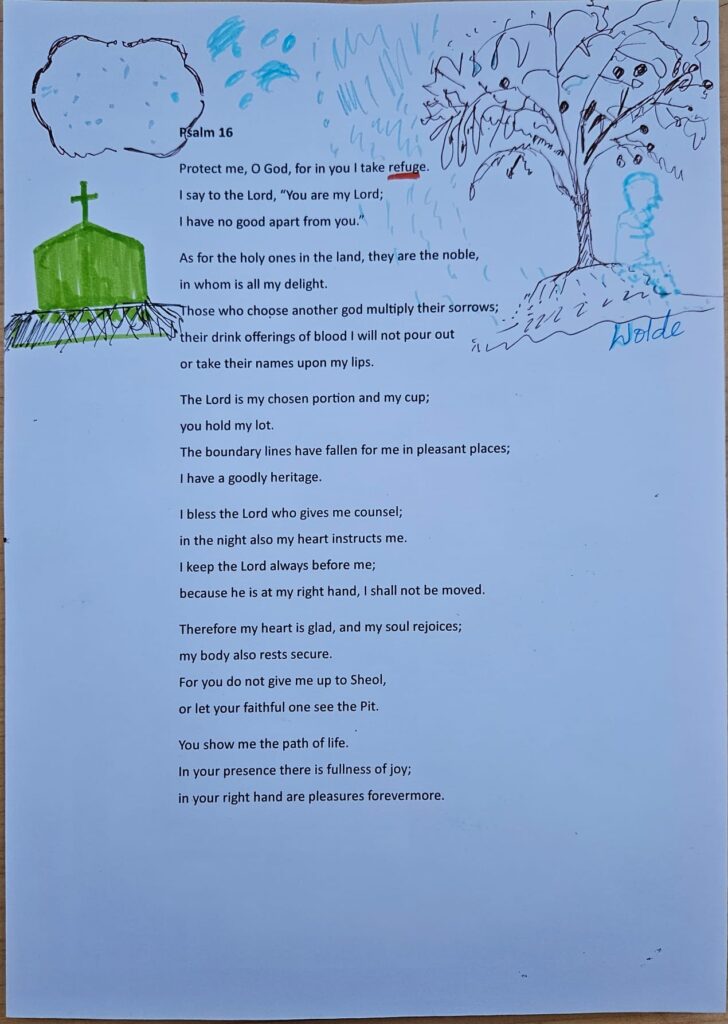

1. Rooting: Belief, Practices, Values, Everyday Life.

As I mentioned in the introduction, my spiritual appetite was paused for so long, except for an interest in studying religion because of its significant impact on society. However, as my curiosity deepened, particularly after I joined the College of Interreligious Studies, religion became a more regular part of my thoughts and academic reflections. I can even say that my spiritual life has gradually begun to grow.

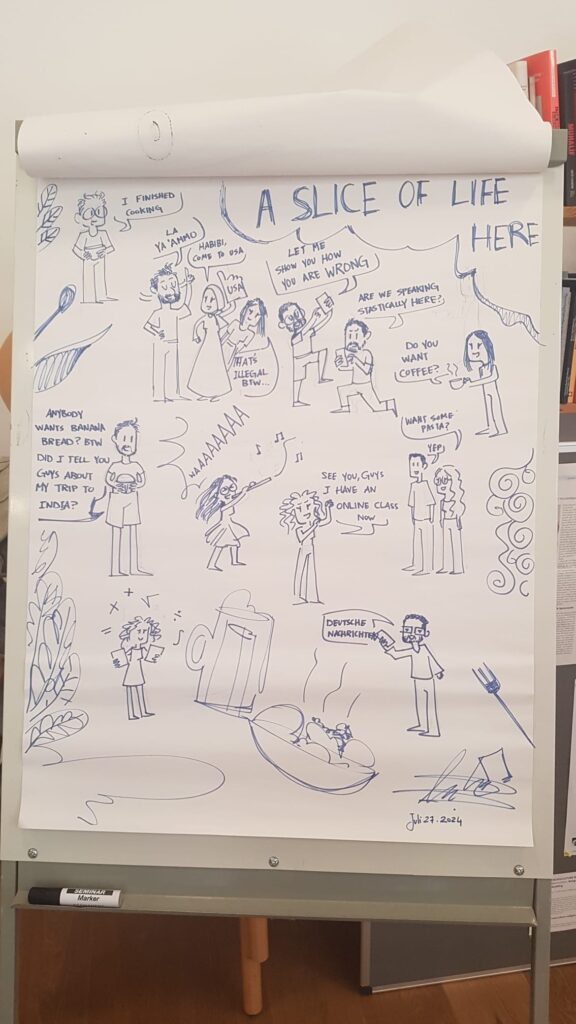

The structured lectures, weekly Friday discussions, visits to religious sites, and countless informal conversations in the kitchen with fellow students from Austria, Zimbabwe, Ecuador, Türkiye, Taiwan, Italy, Ethiopia, USA (Turkish roots), Turkmenistan, Nigeria, Iran, Germany, Syria, Jordan, and Belgiam (Moroccan roots) enriched my understanding of interreligious and intercultural dynamics. Food, attire, holidays, and even global news served us as entry points for meaningful dialogue.

Since June 2024, I have also regularly attended the “Prayer, Dinner, and Community” program hosted by KHG TUM (the Catholic University Community) next to St. Bonifaz Monastery in Munich. Each Tuesday, we gather for prayer, church music, a shared meal, and games. Participants come from diverse faiths and cultural backgrounds and can pray together, if they want, in their languages and traditions. I often recite parts of the Oriental Tewahedo Orthodox daily prayers (ፀሎት ዘወትር) in Tigrigna, usually in silence.

Inspired by some of the lectures on Yoga philosophy and meditation under the Asian religions dialogue, I started to enjoy practising yoga rarely.

This experience has been profoundly enriching on a spiritual level. It inspired me to reconnect with the Tigray Orthodox Church in Munich, where I began attending Sunday services. At the same time, I felt a deepening pull toward exploring Orthodox Christian theology in greater depth. What began as an interest has grown into a true vocation, leading me to pursue a Master of Theological Studies (MTS) online at the Hellenic College Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology in the United States as of August 18, 2025.

2. Awareness: First Encounter with Another Religion

My first encounter with people of another religion, or even with the concept of “another religion” beyond Oriental Orthodox Christianity, dates back to my early childhood. In my home area, the smallest administrative unit (Tabia – ጣብያ) included several villages. One of them, Adihano (ዓዲ ሓኖ), which is my village (ቁሸት), is inhabited by both Orthodox Christians and a minority Muslim population.

Even before I met any Muslims, I had heard about them through conversations at home. I was told, for instance, that we should not eat meat they had slaughtered, and they would not eat meat we had prepared. I was also told that they worked on days we considered holy, which was believed to bring God’s anger (Me’at) and result in punishment, such as floods, devastating windstorms, or heavy, stony snowfalls. They were sometimes blamed for such unfortunate natural occurrences.

Other circulating stereotypes included that they loved sweets, were skilled merchants (especially in towns), trustworthy shop owners, and well-known traditional weavers (ኣለምቲ) and tailors (ሰፈይቲ). These impressions, both positive and negative, shaped my early perception before I ever knowingly met a Muslim.

Later, I encountered Muslims in many everyday contexts; in grade one at school; at the market where my father took me to buy clothes and exercise books, at church funerals, where Muslim elders, identifiable by their religious hats, at the grindmill with Muslim mothers and youth, etc. On our way to the Shire market, while passing by a mosque about a 50-minute walk from our home, I would hear the adhan (ኣዛን), the call to prayer, and more loudly from the tower speakers of Bilal Mosque in Shire Endasilase, the town named after the Church of the Holy Trinity.

Other encounters: Jewish Synagogue and Catholic Women’s Monastery

In addition to my earlier encounters, I also had the opportunity to physically visit and engage with other faith centres after arriving in Munich and the European Union.

3. Questions and Opening Moments: Particular Touching Encounters & Openings

I remember the emotional tension and caution we were taught as children, not to be tricked into or mistakenly eat food prepared by a Muslim if it contained meat. Doing so, we were told, could amount to conversion, and the only way to repent was through confession to one’s personal spiritual father or, in extreme cases, rebaptism. At least, that was my understanding growing up. That belief held until university, when I found myself sharing lunch boxes that included meat with a Muslim classmate during the first summer break. It was a weird feeling at the moment but never worried about mixing foods afterwards.

Of course, I had already learned about the major world religions in high school through civics, ethics, and history textbooks, and I had also heard about Catholicism and Judaism from locals. However, in our local area, it was primarily Orthodox Christianity and Islam that shaped the religious landscape. Protestantism was a new phenomenon, especially for those from rural areas, and any rumour of conversion was viewed as a sign of betrayal and a sinful act. To convert was to risk becoming an outcast.

At university, I met many believers from different religions. I no longer feel uneasy when I meet someone of a different faith. Still, I recall a challenging personal encounter: a distant relative of mine converted to Protestantism, and I risked showing her friendship and affection in public, as she was rejected by many relatives and locals. That was a tough, eye-opening experience.

Afterwards, I attended a few sermon services at one of the Protestant churches in Mekelle (Tigray), listened to preaching at a Seventh-day Adventist church around Ambassador area in Addis Ababa, and bought a copy of the Holy Quran in Amharic from one of the shops around the grand Anwar Mosque compound in the capital; just to get a glimpse of what these religions are about.

4. Interreligious Dialogue: Motivation, Interests and Encounters

I was initially drawn to study and engage in interreligious dialogue because of the significant role religion plays in society. However, my motivation has since deepened, as I began to know and appreciate the rich perspectives, shared values, and differences among various faith traditions.

I was particularly interested in the discussions and exchanges we had in the kitchen with an Iranian Shia Muslim with a philosophical lens, a Moroccan-Belgian with a curious mind, a devout Catholic from Ethiopia, a kitchen police from Turkemistan and an Austrian catholic who kindly invited us to his wonderful parents’ home in Salzburg, served us a delicious food and house-made wine, and introduced us to a fascinating medieval-style Krampus ritual festival.

I now feel better in engaging with prayer and yoga as practices, hoping that I will get inner peace and improve my focus. Interestingly, I also feel an increasing pull toward reconnecting with the spiritual practices of Orthodox Christianity.

5. Point of Contact & Double Networking: Finding Commonalities

During my time at the College of Interreligious Studies and through my engagement with religious studies, I have come to appreciate the many commonalities shared across different faiths. Most of us, regardless of tradition, believe in a divine power or God. We claim to have values such as compassion, justice, and the protection of the vulnerable. Among Abrahamic religions in particular, we find a common Point of Contact of origin in the figure of Abraham.

There are also practical similarities: many faiths observe dietary laws, as seen in Orthodox Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Practices such as prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, and chanting are common spiritual expressions found in various traditions.

These shared beliefs and practices provide important points of contact that can foster interreligious collaboration. I believe we can build effective networks around cross-cutting issues, such as joint research, social justice, and peacebuilding, through what is called double networking: cultivating both intra-religious accountability (understanding and representing one’s own tradition authentically) and inter-religious dialogue (engaging others with respect and openness).

For my part, I feel the need to deepen my own understanding of the Oriental Orthodox tradition, specifically the Tewahido Church of Tigray/Ethiopia and Eritrea, to meaningfully contribute to such dialogue. That was why I decided to continue pursuing a Master of Theological Studies.

6. Transformation: Anything Changed?

I now approach religion seriously. I engage people on social media with greater interest and appropriate context. I have developed an interest in practising yoga and am inclined to enjoy moments of silence and concentration during prayer.

7. Evaluation: Lessons, Spiritual (otherwise) Importance

I have realised how little I actually knew about other faiths, their doctrines, traditions, and rituals, and how much similarity and difference exist between them. This introductory awareness has shown me that understanding each other’s beliefs is essential to avoid wild speculation and harmful prejudices. At the same time, I remain puzzled by the contradiction between the ideals that religions preach and the harmful actions that people commit.

My own spiritual life is still unfolding. At this stage, it feels like a “foot-in-the-door” moment. I am not yet sure if I am fully in or still outside. Whether this renewed connection to my Orthodox Christian faith is a passing phase or the beginning of a deeper transformation is something time will reveal.

Nonetheless, my engagement in interreligious studies, including encounters with people of other faiths and centres, participation in spiritual exercises and community engagement at KHG, as well as attending the Spiritual Ecology Winter School sessions, has been an essential step in my journey. These experiences have deepened my understanding of religion, which in turn informs my academic and research work at the intersection of media anthropology, hate speech, violence, gender, migration, and the broader role of religion in society.

I graduated with a Certificate in Interreligious Studies on July 23, 2025. Following that, I have joined the Institute of Domestic Violence, Religion & Migration (IDVRM) as an Honorary Research Associate (volunteer work) for one year, continued further theological studies, and initiated an action research project on Ethiopian diaspora Church splits following wars and identity politics. These are, I believe, immediate benefits and experiences from the program.

Picture 17: Photovoice presentation & certificate award (Prof. Martin, Woldegiorgis), 25 July 2025.

8. Intra-religious dialogue: Did I tell anyone about my current spiritual and religious status?

I did tell others about my current status, though mostly indirectly. I have shared parts of my spiritual journey and thoughts on religion through my social media posts. Some of my reflections have been received positively, while others have sparked sarcasm and skepticism.

For example, I posted photos and videos from the celebration of St. Michael's Day on June 21, 2025, at the Tigray Orthodox Tewahedo Church in Munich. These posts on Instagram and TikTok received significantly more views and engagement than usual, with mostly positive comments. However, when I shared updates on Facebook about studying religion, some responses included sarcastic remarks and dismissive attitudes. The mixed reactions showed me the complexities of intra-religious dialogue and how personal religious experiences can be met with curiosity, support, or resistance, even within one’s own community.

********